We need to pay more attention to the epidemic of suicide

Arthur C. Brooks

January 24, 2020

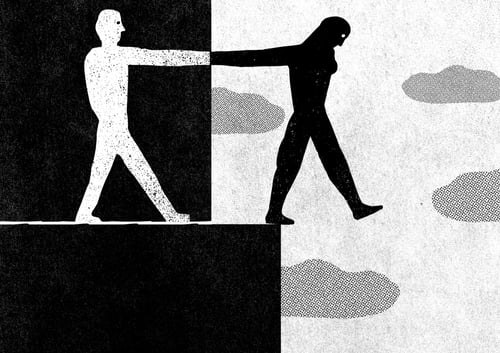

On Friday, Washington was the site of the March for Life, an annual event that focuses largely on abortion, one of the nation’s most controversial issues. There is another life issue that we should pay attention to this year as well, one that might help unite people across the political spectrum: the epidemic of suicide.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 47,173 Americans killed themselves during 2017, which is higher in both number and percentage of the population than at any time since the CDC’s earliest published statistics in 1950. Today, there are two suicides for every homicide death, and 17 percent more suicide deaths per year than deaths from motor-vehicle incidents.

These facts are completely public, yet I am willing to bet that many readers find them very surprising. Despite the hard work of a few government agencies and nonprofit groups, we are largely silent on this subject as a nation; it isn’t something we discuss in polite society. It is shrouded in shame and fear. Meanwhile, the suicide rate quietly climbs, year after year.

Suicide affects all ages and demographic groups, but three particularly stand out. The first is women and girls between the ages of 15 and 24, who have seen the largest percentage increase — nearly double — in suicide deaths since 2000.

What is the cause of this spike? A leading scholar trying to answer the question is Jean Twenge, a social psychologist at San Diego State University. She does not mince words: “All signs point to the screen.” As she wrote in The Post in 2017, teens who spend five or more hours per day online were 71 percent more likely than those spending just one hour per day to have at least one suicide risk factor.

The second group couldn’t be more demographically different: men between the ages of 45 and 64, who make up the biggest number of suicides — 12,371 in 2017. The group represents about 6 percent of the population but accounts for more than a quarter of the suicides; the rate is up 45 percent since 1999. Most of the suicides in this middle-aged group involved guns, a method that is almost always lethal.

We are shocked when we hear about the suicide deaths in recent years of celebrities such as comedian Robin Williams, chef and television host Anthony Bourdain and — especially poignant in my line of work — the much-honored Princeton economist Alan Krueger. We ask what it was about their unusually high-achieving lifestyles that led to this outcome. The statistics suggest that this is probably the wrong question. These men were just prominent cases of what is happening among ordinary middle-aged men (and, to a lesser but still alarming extent, women) across the country every year.

The third group is made up of older men, age 75 and over. The raw number of suicides is much lower than middle-aged men (3,447 in 2017) given that they are a small percentage of the population, they have the highest likelihood of suicide at 39.7 per 100,000 people (vs. 14.0 for the population as a whole).

We don’t know what is driving the suicide increases among middle-aged and older men. It seems particularly strange to most people, because we rarely think of adult men as emotionally vulnerable. However, there is growing awareness of the despair induced by economic trends rendering many men economically superfluous, the loneliness in a generation marked by divorce and non-marriage, and the declines in religiosity among baby boomers and Gen X.

But there are other possible culprits worth considering as well. Kay Redfield Jamison, in her seminal book “Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide,” writes about the uniquely deadly combination of rampant untreated depression and drug use. And not just illicit drugs; this includes prescription sleep aids — the use of which is increasingly common — which research shows dramatically increases the likelihood of intentional self-harm.

Julie Phillips, a sociologist at Rutgers University who has written extensively about middle-age suicide, identifies yet another factor, which is a growing social acceptance of suicide (especially, as the author shows, among those who are male, white, highly educated, nonreligious and politically liberal). While Phillips notes that for most Americans, suicide is still considered taboo, social acceptance has risen by more than a third from the 1980s through the 2010s. Increasing acceptance, especially when reflected in the media and on the Internet, can affect the decision of a person in crisis.

To turn the tide on this crisis, in addition to better identification and treatment of suicidality, we urgently need to raise public awareness and shift the direction of public opinion on suicide in the United States. This is far from impossible; we’ve done it before in the past few decades in other cases, such as traffic fatalities.

Through major public-service campaigns, it became public knowledge that people were avoidably dying in huge numbers on the roads. Seat belts and other safety features became normalized, and then legally required. Drunken driving went from something people chuckled at to something people found deplorable. The result? Traffic deaths have fallen by about one-third since the early 1970s, despite a massive increase in the number of drivers. These lessons must be studied and adapted for a similarly concerted campaign against suicide.

It is especially important to remember that, unlike so many other issues, suicide is not someone else’s problem. The epidemic is remarkably democratic. Your family is not safe. There is no gated community or police force to protect us; wealth and education are no defense. The threat is already inside our homes.

We are all in this together. Will we act before more lives are needlessly lost?